Science communication skills: our top 10 tips

As a scientist, how can you promote your research without selling out? In the world of academia, most scientists would cringe at the sound of the word “sell”. Surely, the science should be able to speak for itself! However, if we take a closer look at what “selling” actually means, it has wider implications that you may not expect: listening, influencing or making unexpected things happen. By communicating effectively about your research, you are not only doing a great service to the general public and your peers but also your own work. Here are our top 10 science communication tips to bear in mind.

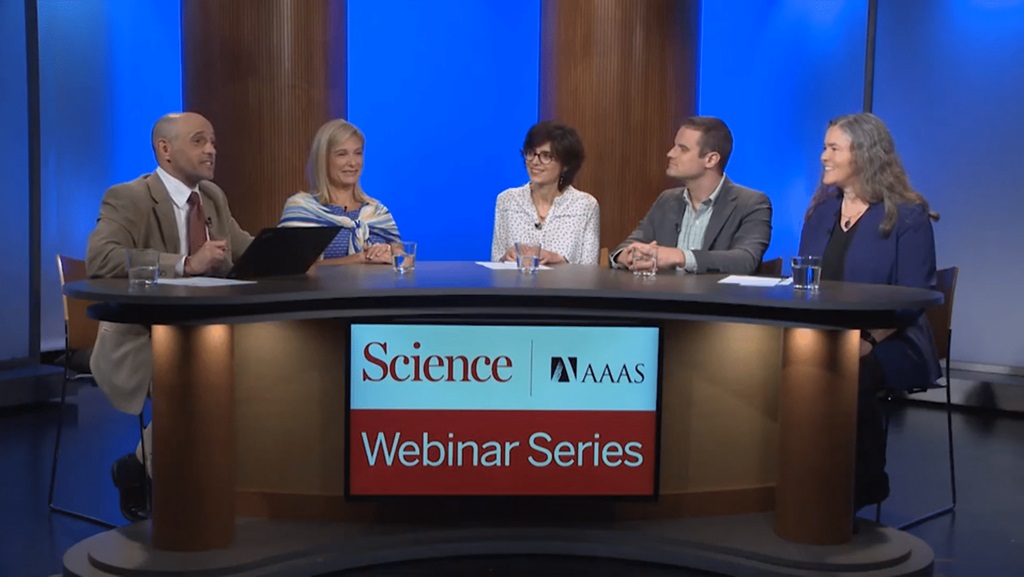

Science Magazine held a webinar dedicated to science communication. This round table, filmed in Washington, brought together a panel of experts on the subject. For an hour, four speakers discussed how to improve the way you communicate about your research to peers and the public. Here, we provide you with our selection of the top 10 tips from this event.

1. Understand your audience

As a scientist, you were no doubt trained to build up evidence and to support your arguments with meticulously thorough explanations. But who is to say that your public wants or needs to know everything? They might be more interested in certain aspects of your project than others. As Matthew S. Savoca, postdoctoral researcher at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University, states: “in science communication, a speaker should adjust the way they explain their work depending on the audience”.

When you start preparing your speech, you should be thinking about who your audience is. Put yourself in their shoes. The general public is interested in how your research affects their lives or society today, tomorrow, or in ten years’ time. Funders are usually interested in how they may get a return on their investment. Your peers will want to know more about how you work, what your findings are and the possibility for future collaborations. Industry partners will look for technologies that can help propose products or services that will become a commercial success. Make sure you understand what your audience is interested in and adapt your communication accordingly.

2. Build your message

In science communication, you will regularly come across complicated topics. Your audience might not remember everything you have said or written once your communication is over. So, you need to define what you want them to retain. What single idea should they leave the room with? This will be your message.

Alexia Youknovsky, CEO of Agent Majeur, science communication agency, recommends to figure out who your audience is and what they expect from your talk. You then need to think about your own objectives: what do you want to achieve? “By combining all that information, you can define what message you want to convey”.

3. Connect with the public

To successfully communicate, you first need to draw the attention of your audience and then connect with them. According to Laura Lindenfeld, director of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, you need to ask yourself the following questions in order to communicate with your audience: “who is the person I am talking to? Why should they care about my work?”. Effective science communication is not only about facts and figures, but also about empathy.

She adds: “we usually make this assumption that human beings are thinking beings who also feel. But we are feeling beings who also think!”. In order to connect with your audience, you should convey emotion, even when talking to your peers. If you want to forge a link with them, you can make them laugh or surprise them, for example.

4. Tell your public a story

You could also choose to communicate using a story. Storytelling is a very specific way of evoking emotion. Stories are not just for children at bedtime. Just think about how much time adults spend reading novels or watching movies. Structuring the way you talk about your science into a story is a highly effective way to get your message across. Stories are also remembered more easily than technical explanations.

“Storytelling humanises scientists”, says Laura Helmuth, Health, Science and Environment Editor at The Washington Post. Almost all research projects can be explained using visuals, analogies and metaphors. You can also decide to share a personal or professional anecdote. Try to find the stories that suit your topic!

5. Talk to journalists

Having access to a large public above that of your own network, can seem difficult but can also be very rewarding. In this respect, interacting with a journalist can be very effective. Before meeting a journalist, prepare yourself well. Start by understanding why they have contacted you and why they care about your research. Make a list of the questions you may be asked and prepare short and precise answers.

As Laura Helmuth suggests, any “information will get distilled when published”. You should try to do this exercise yourself rather than letting journalists doing it for you. When talking to journalists, it is also essential to be quick to respond and, if possible, generous with your time. She adds: “it’s a public service to your field, to your own research and to the audience”.

6. Make your science understandable

One can never popularise enough. Often, in scientific communication, a speaker or writer overestimates the public’s knowledge of a given subject. We name this phenomenon the “curse of knowledge”. The concept is simple: the person with expertise on a given topic will have a hard time explaining it to ordinary people. Laura Helmuth says that you should work on the assumption that “the people you are addressing have a million things that require their attention and concentration”. Therefore, try to popularise your speech.

As complex words may lead to misinterpretation and confusion, in scientific communication, jargon should be avoided. It is better to use simple words and sentences instead: this will help your public to stay focused on your reasoning. Keep in mind that for non-scientific audiences, most of the concepts you are going to discuss sound like a foreign language. “Remember the words that you once didn’t know Capture that memory of being confused” and ask yourself: “how can I say this differently?”

7. Deal with controversial topics

When you are communicating about a controversial issue, expect your public to have preconceived ideas or assumptions about it. In this instance, you should try a new approach rather than simply bombing them with facts.

Do not to assume that your audience is “hostile”. Instead, try to remember that it is easier to listen and trust a speaker who doesn’t talk down their nose at you. By respecting your audience’s opinion and demonstrating a willingness to engage with their questions, you can open up a dialogue more easily. With this in mind, try to see that controversy can have positive implications. And, you never know, it may even help you shed new light on your own research project.

8. Embrace uncertainty

Science is a process of building up evidence. What is true today may not be as accurate tomorrow. Uncertainty is inherent to science and research. As a matter of fact, “from a scientific perspective, uncertainty is the exciting part” (Matthew S. Savoca). Remember that, regardless of uncertainty, a researcher should be able to speak from a place of authenticity and accuracy. Hence, “embracing uncertainty” and not “shying away” from it will help you be more transparent and respectful towards your audience.

As a scientist, you should also shed light on the results that you are sure of based on your evidence. The words you choose should convey that idea of self-confidence. If you’re giving a presentation, it is also important to pay attention to your non-verbal communication. That is to say, your presence and your voice – what your audience sees and what they hear.

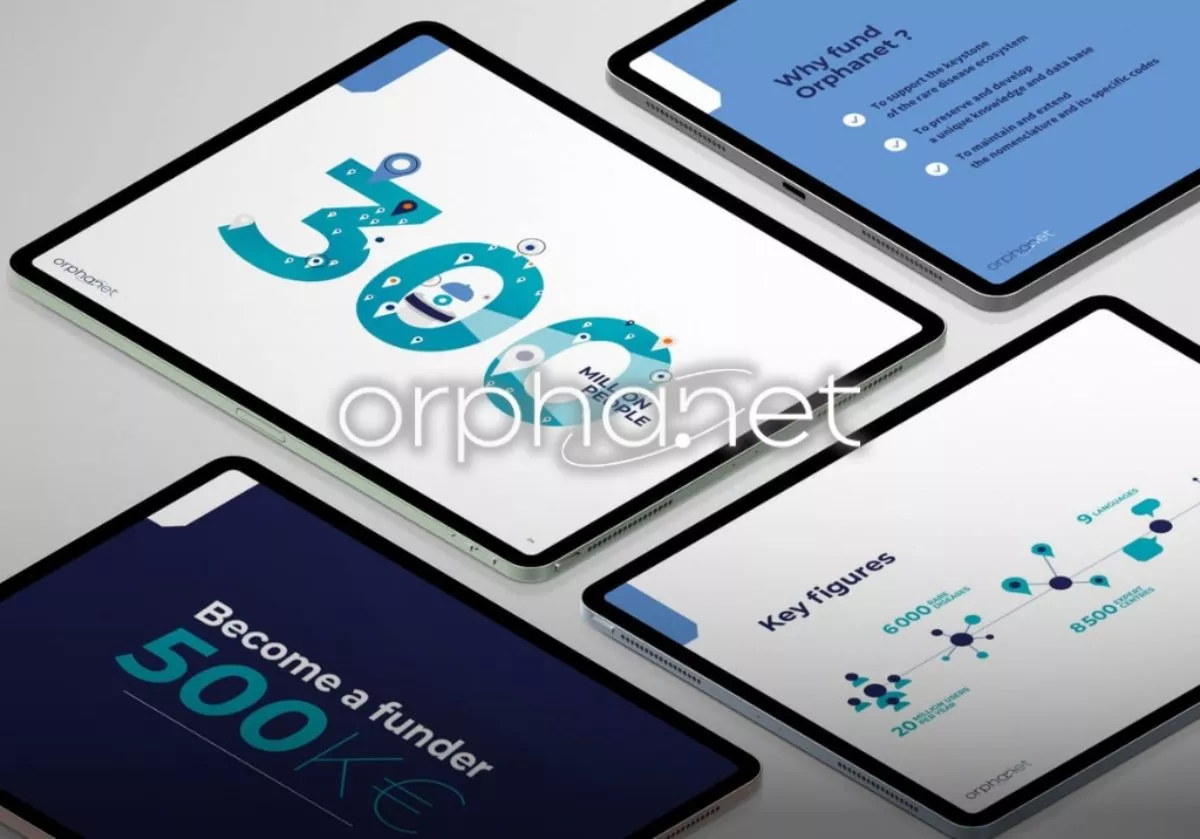

9. Mix communication channels

Articles, conference talks or the press may be considered as “traditional” tools for communicating science. However, in the past years, other tools such as social media, blogs, podcasts or videos have evolved to become important communication channels too.

And they are not only a fantastic way to communicate to the general public, they also provide the opportunity to exchange with fellow researchers and build scientific communities. When communicating, you should think about combining “traditional” tools and with newer ones. This will allow you to communicate in an interesting and dynamic way, broadening your audience’s experience.

10. Learn to communicate

Science communication is a skill that can be learned. Part of the way you may learn “[…] is by reading a lot, notice what sort of articles are interesting to you, what sort of quotes amplify a story or make something clearer to you when you’re reading somebody else’s work.” (Laura Helmuth).

You can also decide to attend a science communication training course, such as those proposed by Agent Majeur using our SELL Method®. You can be trained on public speaking: for example how to talk at a conference or how to present a research project in three minutes. Courses can also help you to improve your written communication: how to write a PhD thesis, a scientific article, or how to use social media.

Communicating science can spark interest and enthusiasm, help reverse negative attitudes and encourage support for your research and institution. It may be also be a great way to gain a deeper understanding of your research and its applications. So, yes, science can be sold and it is more positive than you may think.

You can watch the full webinar, sponsored by Fondation IPSEN, on the Science magazine website.

We have selected other key moments of the online seminar for you. You can watch our science communication tips on our YouTube channel.